Race and the streetcar suburb

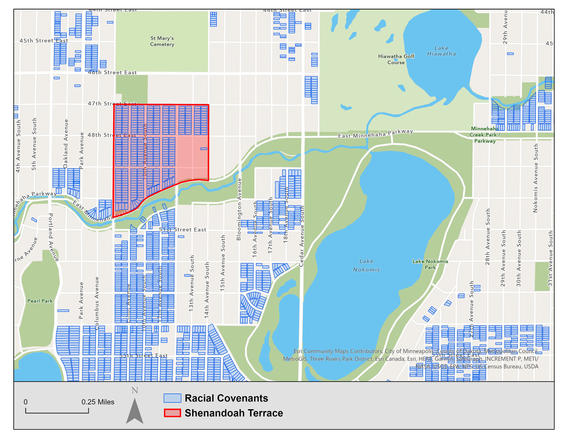

In the 1920s, the owner of a large chunk of land in south Minneapolis decided that it was time to benefit from rapidly rising property values. This land--which was adjacent to Minnehaha Creek--had been used to to bury the dead, graze cattle and house orphans. Strategic investments by the Minneapolis Park Board and the Twin Cities Rapid Transit Company had rendered it a prime location for a new streetcar suburb.

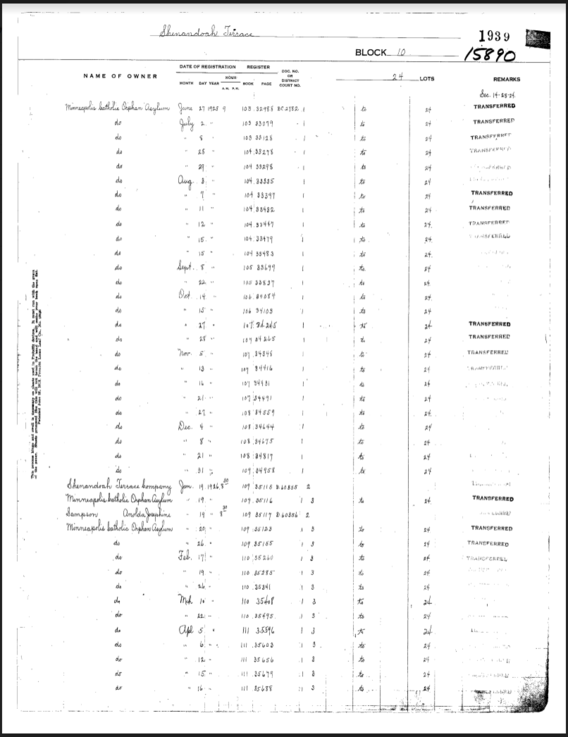

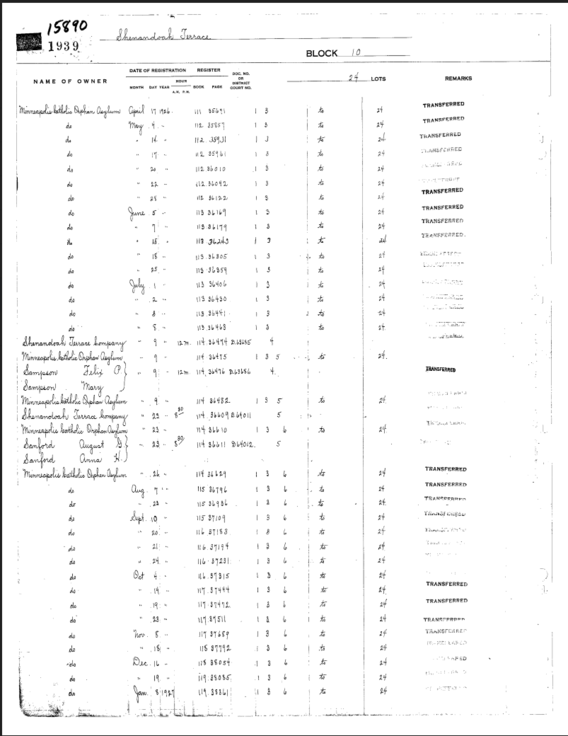

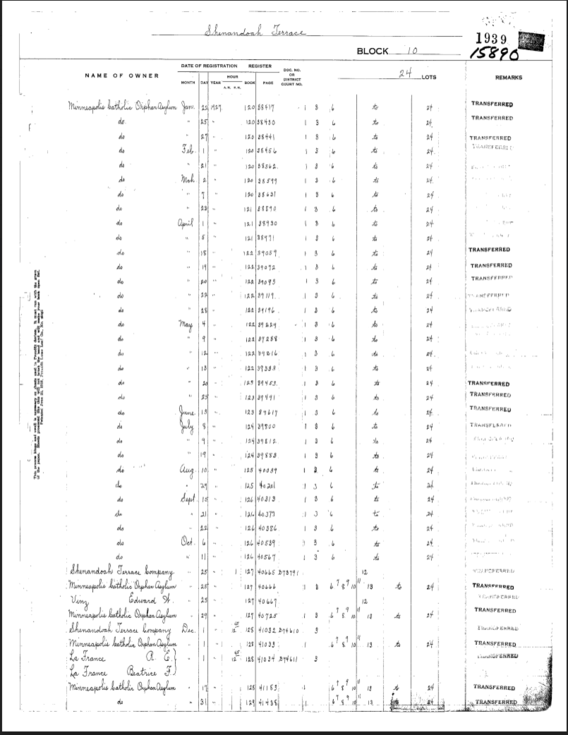

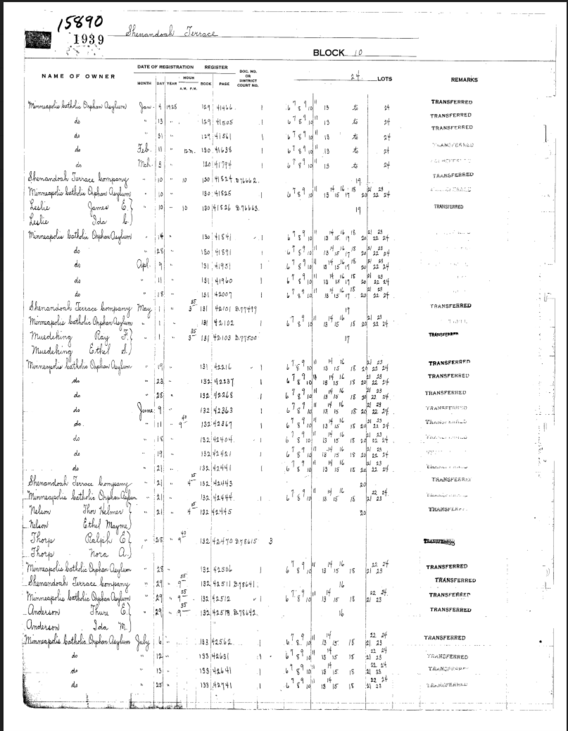

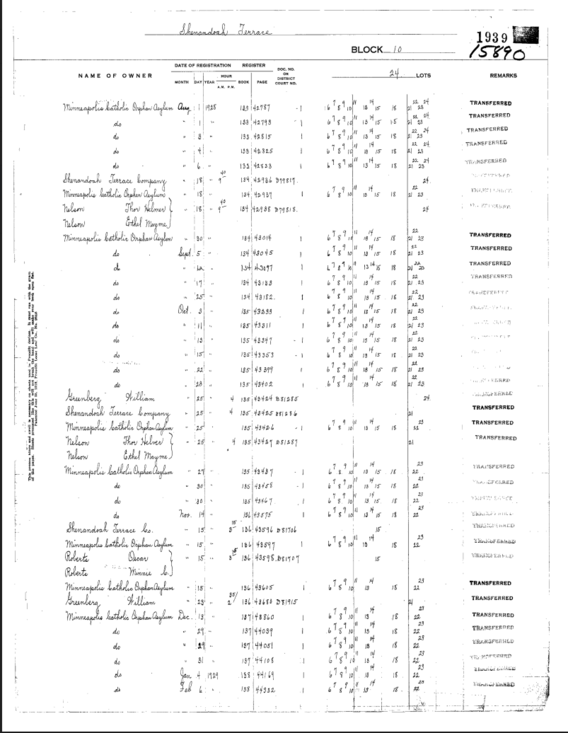

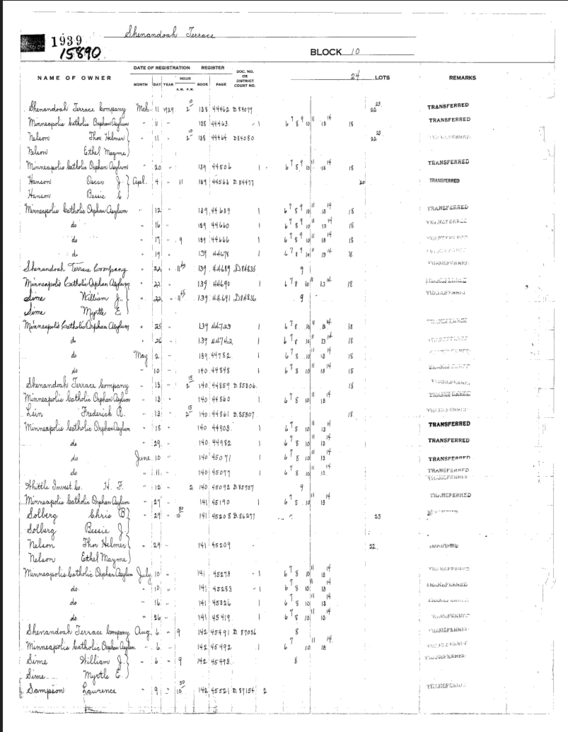

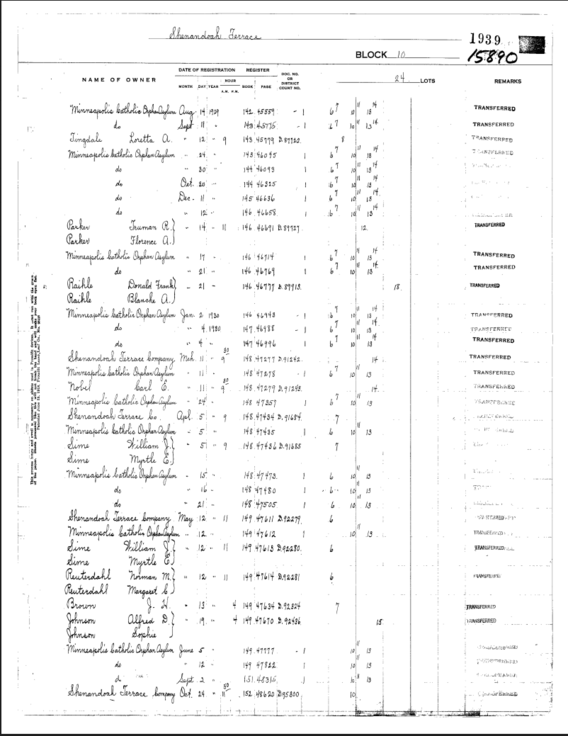

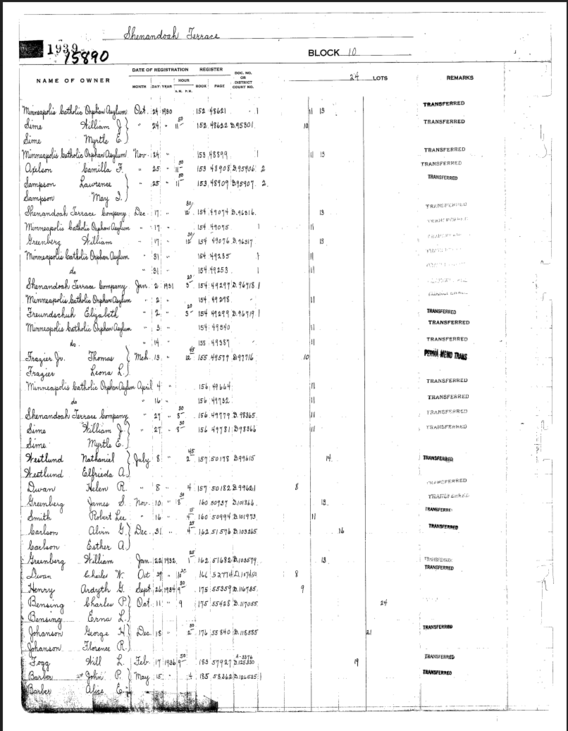

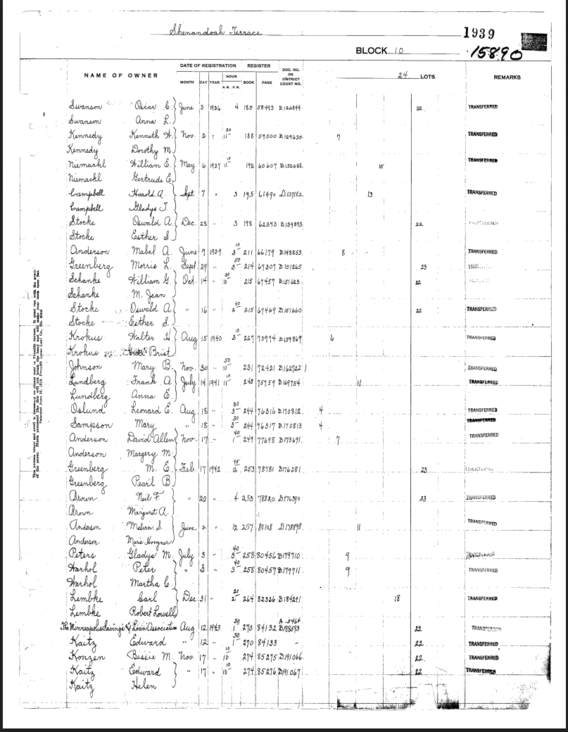

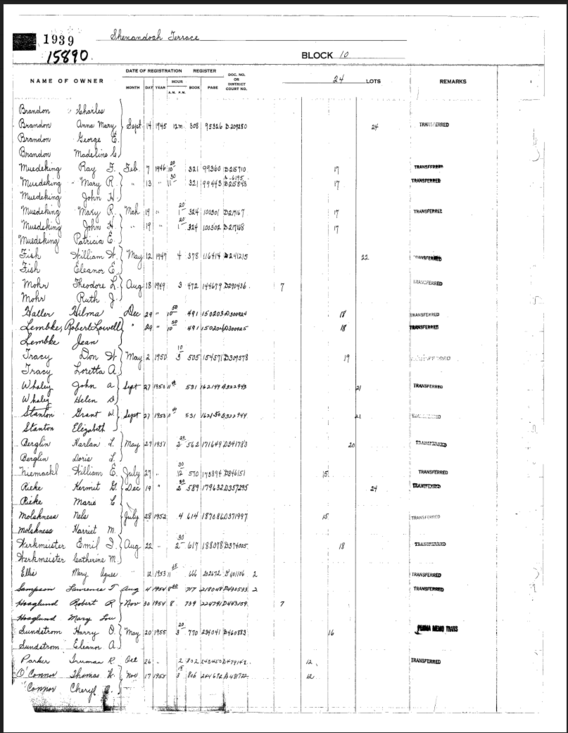

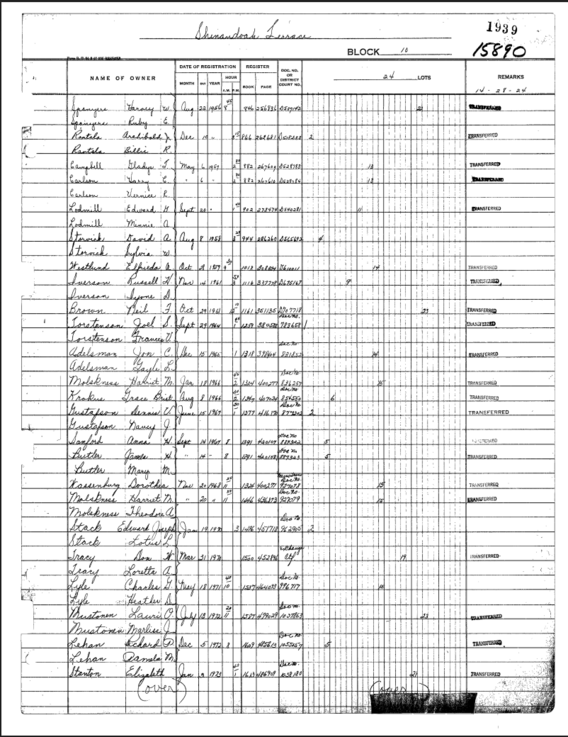

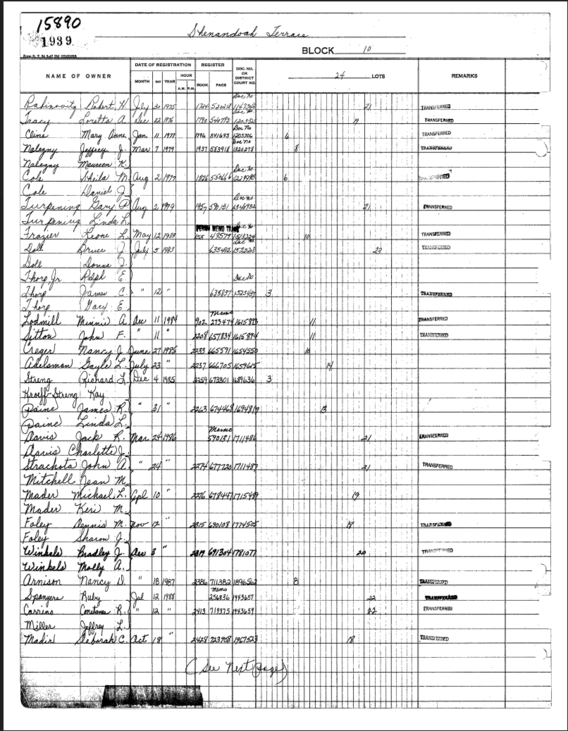

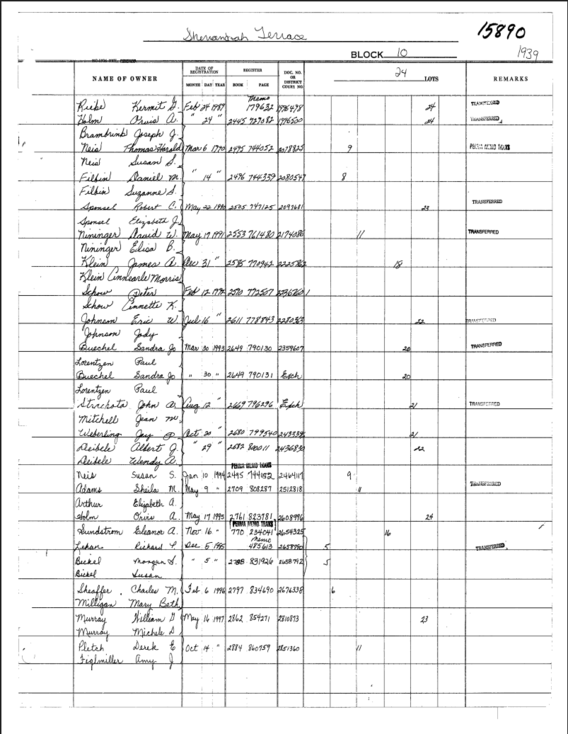

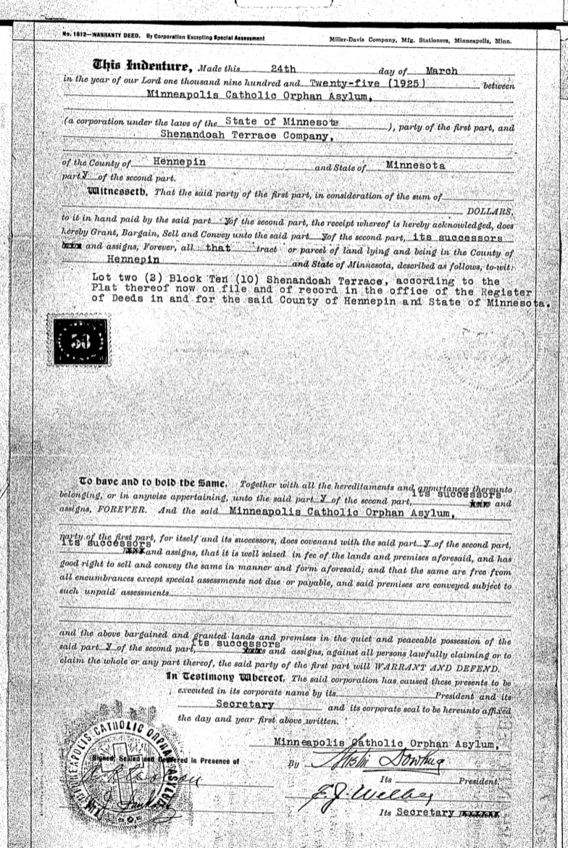

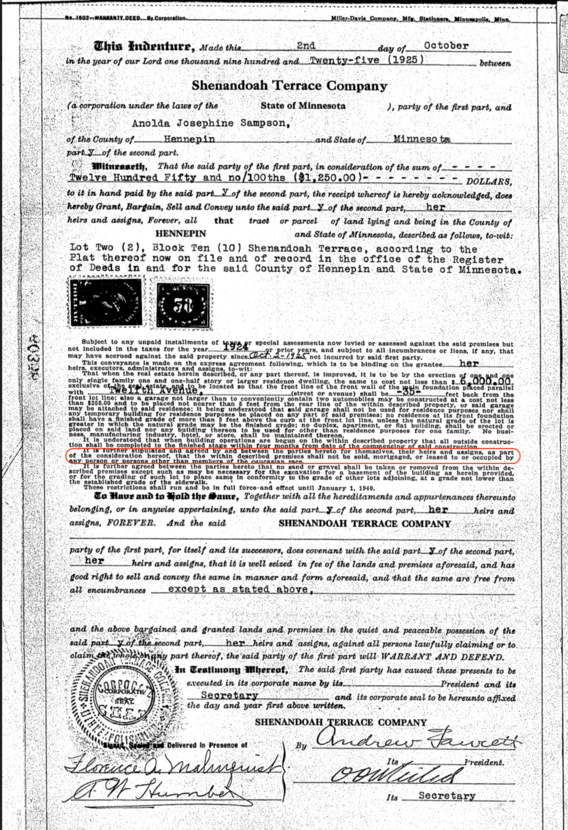

This landholder decided to sell all but 10 of the acres it owned between 46th street and Minnehaha Creek. It worked with real estate developers to carve up the remaining 68 acres, dividing the hills and woods of the landscape into 327 residential lots. The platting of Shenandoah Terrace transformed this bucolic setting into a grid for residential development. It also drew racial boundaries in the landscape. This text was attached to each of these new residential parcels:

[these] described premises shall not be sold, mortgaged, or leased to or occupied by any person or persons other than members of the Caucasian race.

The landowner responsible for blanketing Shenandoah Terrace with racial covenants was the Catholic Boy’s Orphan Asylum, which had been established at the direction of Bishop John Ireland in 1886.1 This decision ensured that this neighborhood, which is bounded by Chicago Avenue and Minnehaha Parkway, would be inhabited by white people for decades. It remains one of the whitest areas of Minneapolis, more than 50 years after the passage of the Fair Housing Act.

Photoprint of the Catholic Boy's Home via the Hennepin County Library Digital Collections.

The Catholic Boy’s Orphan Asylum had been created by a group of community leaders who were inspired by Bishop Ireland’s declaration that “justice and necessity” required his parishioners to carry “the burden of orphaned children.”2 Supporters donated land adjacent to the modern-day intersection of 46th and Chicago Avenue, raising the money to build what was described as a “baronial castle,” that was located on “78 acres of rich ground, partly wooded and sloping from a knoll down to Minnehaha Creek.”3 The Sisters of St. Joseph “taught the lessons of life” to the boys “in the pure air and attractive surroundings” where this small community supplied its own food by tending gardens and keeping dairy cows.4

During the first several decades of its existence, the Asylum was known for its policy of racial and religious inclusiveness. A journalist who visited the orphanage in 1905 wrote that “creed, race and color are not questioned: non-Catholics are received with as warm a welcome as those of the Roman faith, and black boys and white share alike the protection of its beneficent walls.”5

Observers made virtue from a necessity, touting the advantages of caring for the orphans “far from the ills of city life.” But the orphanage was likely located in this swampy section of the city because land was cheap. For many years, the Asylum’s closest neighbor was a large cemetery for nuns.

The early twentieth century brought rapid changes to what had once been seen as a remote hinterland. A powerful agent of change was the Minneapolis Park Board, which made ambitious investments in state-of-the-art green spaces in this section of the city. After acquiring a swamp known as Lake Amelia in 1907, the Park Board dredged the wetland and renamed it Lake Nokomis. The new lake connected to the recently constructed Minnehaha Parkway, which snaked along one boundary of the Catholic Boy’s Orphan Asylum. Another driver of development was the Twin Cities Rapid Transit Company, which extended the streetcar line on Chicago Avenue past Minnehaha Creek. This made the area that would become known as Shenandoah Terrace easily accessible for people who worked in the central business district.6 These investments in green space and transit converged to make this area enticing for would-be homebuyers.

Shenandoah Terrace situated in south Minneapolis covered in racial covenants.

Those responsible for the operation of the Asylum sensed opportunity. They teamed up with local real estate developers to sell off much of the newly-valuable land surrounding the orphanage, hoping to convert the rolling woodlands into cash that could support their mission. The decision to sell was sparked by investments in the urban infrastructure. But the way the transaction was conducted was shaped by rapidly changing ideas about race in the urban environment.

Only four years after the reporter from the Minneapolis Tribune had praised the racially inclusive ethos of the Asylum, the editorial board of the Minneapolis Journal called for coordinated action to make Minneapolis neighborhoods all white.7 The introduction of racial covenants to Minneapolis in 1910 ushered in a new era for the city. City leaders were following the guidance of newly influential urban planners and real estate professionals, who argued that healthy urban environments required both plentiful green space and strict racial segregation. The Asylum was surely influenced by this new orthodoxy when it decided in 1921 that it could no longer serve children who were not white. Though administrators blamed the “attitudes of other children” for this shift, this assumption that people of different races could not live together also guided the planning of the real estate development that would swallow up the woodlands that had surrounded the orphanage.8

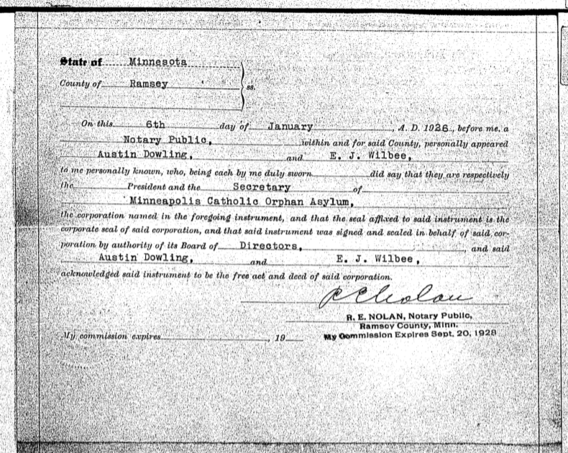

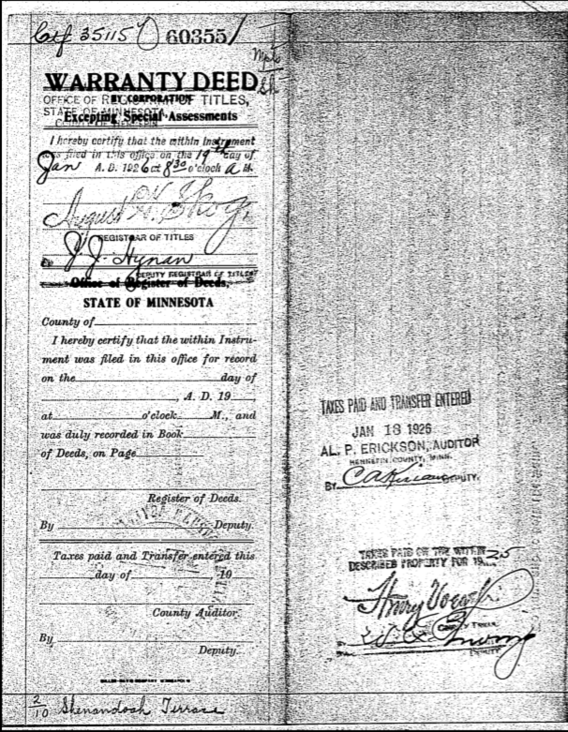

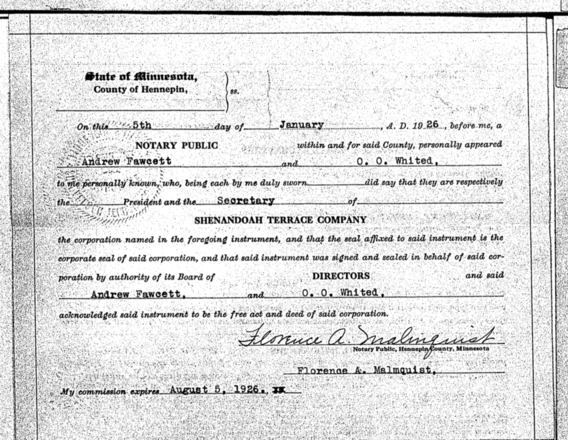

Leaders of the Asylum realized that they could not execute a large-scale real estate development without outside help. So they entered into a partnership with Shenandoah Terrace Company and Estates Improvement, Inc., which were responsible for surveying the 68 acres and laying them out into streets, lots and blocks. As part of this process, racial covenants were attached to each of the new home lots. The paperwork for the Asylum was signed by Austin Dowling, the Archbishop of St. Paul and Rev. E. John Wilbee, pastor of St. Anthony of Padua. They turned the technical business of selling lots over to the real estate professionals, who wrote the exclusionary clauses.

Even though racial covenants were being promoted as the best practice for real estate developers, these church leaders may have harbored some unease about this aspect of the development. By having a real estate holding company attach the covenants before finalizing the sale, the orphanage--and the Catholic Church that administered it--was able to profit financially from racial covenants without having to defend the use of discriminatory deeds.9

The Catholic Church was not alone. Any institution or entity that bought and sold property during the twentieth century in Minneapolis likely participated in this practice of barring people who were not white from inhabiting or owning land. To move forward as a community, we need to acknowledge this historical truth. As James Baldwin said: “as long as you pretend you don’t know your history, you’re going to be a prisoner of it.” So now that we are working towards freedom, where will this new knowledge take us?